The New York Mets have officially won the Yoenis Cespedes waiting game.

After months of playing chicken with Cespedes and his representative agency, Roc Nation, the two sides have settled on a three-year deal worth $75 million dollars with an opt-out clause after the first year. Though the average annual value of the pact is $25 million (which ties him with Giancarlo Stanton and Josh Hamilton for the highest AAV ever for an outfielder), Cespedes will be receiving $27.5 million for the first year.

Immediate gut reaction in Flushing is that this is a coup—exactly the kind of cautious, yet aggressive (if such a thing even exists) deal that Mets fans wanted to see out of general manager Sandy Alderson following a 2015 World Series appearance. Out of this winter’s entire free agency class, Cespedes produced the most Wins Above Replacement (WAR) in 2015 with 6.7, eclipsing David Price‘s 6.4 WAR. Price, as you might remember, received the largest contract for a pitcher in MLB history earlier this winter with a seven-year, $217 million deal. Cespedes was worth more on the field in 2015, and the Mets will now have him secured for at least one year and possibly two more.

There was little question that Cespedes’ bat sparked the Mets’ lineup upon his arrival, and as ESPN Stats & Info points out, the Mets, with Yoenis Cespedes in the lineup from Aug. 1 to the end of the season, posted a .794 OPS, a stark improvement from the meager .664 mark achieved by the club from April to July 31st.

Without Cespedes, the Mets were 53-50 and averaged 3.5 runs per game, and the 2015 season felt like another rebuilding year. With Cespedes aboard, the entire Mets lineup posted a National League-best 5.4 runs per game in the remaining 59 games after the trade deadline. New York won 37 of those contests and cruised to their first NL East title since 2006 while reaching the World Series for the first time since 2000.

Despite his clear and immediate effect on offensive output, front offices were hesitant to hand him a long-term deal, as clearly evidenced by his taking a three-year offer with a week left to go in January. There have long been questions about what kind of player Cespedes really is. Is he more of the low-batting average, high-slugging percentage slugger we saw from 2013-2014? Is he capable of overcoming his plate discipline (career .319 OBP) with acceptable batting average and plus power? Does he belong in center field?

Noteworthy Splits

As much as he was a fan favorite in New York, Cespedes only hit .224/.290/.480 at Citi Field with five homers and seven RBIs as a Met. That’s a staggering figure, considering how much of the narrative of his free agency has been built around “Look how far he vaulted a flawed team into the playoffs!” Regardless, it’s never been a secret that Citi Field is the east coast’s Petco Park. Fly balls go to die at the warning track; that much is commonly accepted.

Anybody telling the story of the 2015 season will inevitably discuss Cespedes’ impact on the NL East race, and it will be almost certain that one of the homers referenced in the discussion took place on the road. For good measure, here’s Cespedes getting acquainted with Coors Field in the form of a three-home-run game.

Since 2012, he’s profiled as primarily a pull hitter, though he does possess some ability to flash power the other way. He’s shown that he has the raw strength to pull home runs, even on swings when he made less than optical contact, but more impressive is his power to the opposite field.

In the above clip of his three-homer game at Coors Field, we see his power at work in three different cases: an opposite field shot on a fastball up and away, a homer to dead-center field on a hanging slider, and, perhaps most impressively, another opposite field shot hit off a low-and-away 80 mph slider…from a lefty.

No disrespect to the other two homers, but the third one shows his phenomenal hand-eye coordination in keeping his hands back long enough to swat a low-and-away breaking ball to the opposite field. That’s a feat in and of itself, as most hitters would find themselves lunging and pulling that sort of pitch, likely grounding it to the third-base side. One can say he was even a little bit off-balance on the follow-through from that swing. He is strong enough to be fooled and still do damage.

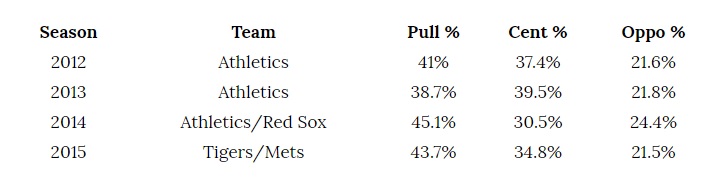

Looking at his pull/opposite-field hitting splits, Cespedes’ 2015 was very much in line with what he’s done in his MLB career since 2012: 42.4% pull, 35.2% up the middle, 21.5% the opposite way.

There’s not much notable fluctuation here, though, interestingly enough, in his spray chart, it seems as though a majority of his flyouts in 2015 occurred in right field. Perhaps Cespedes was making a concerted effort to hit the ball the other way? Given the spacious nature of his home field for 2016, it might behoove him to continue this strategy and focus more on splitting the outfield gaps rather than driving the ball over the wall.

Hitters like Cespedes operate better when they are fixated on opposite-field hitting. A good example would be a young Alex Rodriguez. Their optimal form is when they are patient yet quick enough to let the ball travel deep in strike zone, using their powerful arms to inside-out it the other way. When they’re this locked in, if a pitch is middle-in, they’re also strong enough to swing earlier and definitively pull it for power.

Problems arise when they become homer-happy beyond their hot streak. They ground outside pitches to shortstop, lose confidence in their eye at the plate, and even might look late on inside fastballs. Cespedes is no stranger to these kinds of slumps and is likely better served by looking to mold himself into a gap hitter in the expanses of Citi Field.

It would be reasonable to expect a regression in batting average for Cespedes over the course of a full season; after all, his 2015 batting average on balls in play (BABIP) was the second-highest of his career (.323, just narrowly short of the .326 mark in his 2012 rookie campaign), while his career BABIP up to this point is .304.

The most likely outcome for a 2016 Cespedes is that his BABIP normalizes somewhat. In short, 2015 Cespedes is the ceiling-level example of what happens when he is healthy, playing regularly, and is having favorable luck when he puts the ball in play.

This caliber of production may or may not be sustainable, and if it is, then it’s not for much longer than three or four years, seeing as how he’s 30 years old right now. This may be the strongest reason why the move is currently lauded and popular with the Mets fan base: New York is paying for what should be the best one to three years he has left in his tank before he begins physically declining.

So He’s a Great Hitter, But a Corner Outfielder Posing as a Center Fielder

The metrics and the eye-test will agree; Cespedes looks bulky and out-of-place in center field. Center fielders are supposed to be the captains of the outfield. Range and route efficiency are of the utmost importance, followed by arm ability. Everyone knows about the arm, but his paths to fly balls are suspect.

Interestingly enough, his range while playing 1,022.1 innings in left field in 2015 was 10.9 runs above average (RngR). Fangraphs credits him with 15 defensive runs saved (DRS) for his work split between Detroit and New York, though his total DRS for the entire year sits at 11. That’s because in his 312.1 innings in center field as a Met, he was actually worth -4 DRS while receiving a -1.7 RngR rating. As a left fielder, his arm was worth 6.2 runs above average in 2015. That’s not surprising, as the word on Cespedes’ arm has been out for quite some time now.

Anecdotal evidence aside, the numbers back up the assertion he belongs in a corner outfield spot. But with the Mets clearly unwilling to move Michael Comforto from left field, that leaves center field and right field as the other available options. We have seen why he shouldn’t be a center fielder. Could he instead fit in right field better?

Conventionally, right fielders are big-bodied power hitters whose primary defensive asset is a strong throwing arm. Their range isn’t their strong suit, but the good ones have positive defensive ratings in their corner outfield home. Cespedes fits these attributes, and there’s no question that his arm would play well in right field. If not for his questionable route-taking, he’d certainly profile as a center fielder, but he doesn’t. The best utilization of Yoenis Cespedes’ fielding ability is in right field: an arm-first defender for an arm-first position.

The Complication of Cespedes in a Mets Outfield

If Cespedes were to move to right field, though, what does it mean for the center field job? Do the Mets roll with a platoon of Juan Lagares/Alejandro De Aza or hand the job to Curtis Granderson?

It depends on what their manager, Terry Collins, values in his defensive alignment. Though Curtis Granderson is widely seen as having lost range of his own, he does have more than a decade of experience in center field before signing with the Mets to play right field. His arm was never anything special, but he still possesses speed and can at the very least be counted on to keep the ball in front of him. Granderson was an objectively good right fielder for the Mets in 2015, worth 11 DRS, even registering three runs above average with his arm. Not great, but good. That likely translates to an average-at-best center fielder, one entering his age-35 season while carrying 20+ home run potential.

Sure, it’s not ideal, but it’s a higher upside than a platoon of Lagares and De Aza, who are glove-first, speedy, contact-reliant hitters. No one questions that their platoon is a more defensively secure center field, but their platoon splits render them to be better suited as the fourth and fifth outfielder on the roster, or as two halves to one primary backup outfielder. Lagares in his career has slashed .279/.325/.427 against lefties vs. .254/.286/.340 against righties. De Aza has a career OPS of .756 against righties vs. .657 against lefties. Even at their best, they’re mildly passable hitters without the upside of power that Granderson possesses.

A Potential Tradeoff of Intriguing Proportion

Where Cespedes winds up actually playing is going to greatly affect the defensive value the Mets receive from him. His bat provides a clear boost to the lineup, but playing him in center field regularly would be a mistake. Putting him in the position where he is best fit to succeed will require some creativity, and how Collins chooses to deploy Cespedes will be one of the more intriguing storylines of the Mets’ 2016 season.